This article aims at addressing the age-old question: What happens after you type a URL into a web browser? The use case entails the background details of typing “google” in the address bar. Before we begin, it is ideal to note that ignoring the website’s downtime, the average load time of any webpage is less than 2.9 seconds, leaving each of the processes highlighted below occurring in nanoseconds or less. This article covers an in-depth analysis of behind-the-scene activities from the point a user presses the “g” button up until a result displays on the screen.

User presses letter “g”

The moment the first letter in google (letter G) is pushed, the browser receives the input entry event, and an auto-complete function immediately kicks in. Depending on your browser’s algorithm, various suggestions are presented to the end-user in the dropdown below the URL bar, varying from recently entered, web browser type, recently trending to most entered inputs. In this case, the auto-complete function completes the query to google.com.

The “enter” key bottoms up

Taking the point at which the “Enter” key on the keyboard hits the bottom of its range (called bounce) and debounce, an electrical circuit specific to the enter key is directly or capacitively closed. This closed-circuit allows the flow of minute current into the keyboard’s logic circuit, which then scans the state of each key switch by debouncing the unique electrical noise generated from the switch’s rapid intermittent closure. The electrical noise is converted into a keycode integer (in this case, 13), which is encoded by the keyboard controller for transport between the keyboard and the computer. The transmission channel, generally over a Universal Serial Bus (USB), can also be a Bluetooth connection, or legacy connectivity like PS/2 or ADB

IRQ signal

The moment the processor finds a closed circuit, it compares the location of the most recently closed circuit on the key matrix to the character map in its read-only memory (ROM). A character map, being a comparison chart or lookup table for each key encoding (UTF, ASCII…), signals the processor the position of each key in the matrix and what each keystroke or combination of keystrokes represents. The keyboard, exclusively reserved for interrupt request line (IRQ 1) sends signals on its IRQ, which maps to an interrupt vector by an interrupt controller. The computer then maps out the interrupt vectors to functions uses the Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT) provisioned by the kernel. As the interrupt arrives, the kernel inputs when the CPU indexes the IDT with the interrupt vector and runs the appropriate handler.

CPU message relay

The keyboard’s switch contacts are wired to a microprocessor arranged in an X-Y matrix, constantly beaconing to notice the updated values of the currently opened or closed keys. When it senses the enter key down, it sends a serial code to the PC (single byte for most keys). When it senses a key released that was previously down, the same code with an additional “0xF0” byte is received. The host PC captures these incoming codes and uses them to maintain its map of which keys are up and down. The PC then writes the ASCII code for each new ‘down’ key into a volatile memory buffer where any running application can retrieve it.

For example; ‘A’ – make code 0x1C; break code oxF0,0x1C

Browser input Logic

Browser input Logic

The browser, being equipped with the ability to decipher outputs based on predefined inputs, can process the logic to interpret “https” as HyperText Transfer Protocol (Secure), “/” as slash notation, “@” as email predecessor. In the case where no protocol or valid domain name is specified, the browser then feeds the text entered in the address bar to the browser’s default web search engine (Google, Baidu, Bing). The URL is usually appended with unique texts to notify the search engine of its origination, which in this case, is from a specific browser’s URL bar for a browser-specific rendering during output.

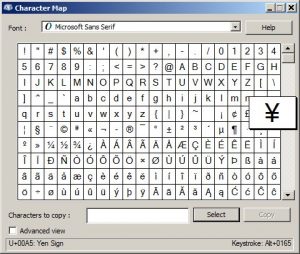

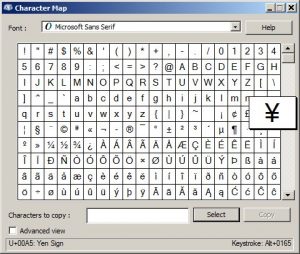

Check non-ASCII Unicode Characters

In the world of Multilingual Web Addressing, where non-ASCII characters are now added to Web addresses, browsers are now able to detect and convert non-ASCII Unicode characters ( a-z, A-Z, 0-9, -,) in hostnames. Since the hostname is google.com here, the Punycode is resolved by the domain name server into a numeric IP address. For encoding, If the string representing the domain name contains non-Unicode characters, the string is converted to Unicode by the user agent (UA). Normalization functions are then performed on the string to remove mismatch. This can include converting uppercase characters to lowercase, reducing alternative representations, and eliminating prohibited characters (whitespaces). Next, UA converts each of the labels (pieces of text between dots) in the Unicode string to a Punycode representation. To differentiate original ASCII labels from non-original labels, a unique marker (‘xn--‘) is prefixed for each label containing non-ASCII characters.

HSTS Validation

The browser then performs a lookup on its internal list of websites that have requested to be contacted via HTTPS only called “preloaded HSTS (HTTP Strict Transport Security)” list. If the list contains the website (google), the browser sends its request via HTTPS instead of HTTP, automatically appending the “s” at the suffix of the HTTP after the certificate authority (CA) is initialized and verified. Alternatively, the initial request is sent via HTTP. However, a website can use the HSTS policy without being in the browser’s HSTS list. This is established when the user’s first HTTP request to the website receive a response that the user only send HTTPS requests, this then forces the browser to establish communications only in HTTPS going forward.

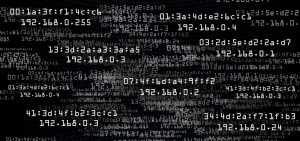

DNS lookup

DNS lookup

The browser then checks if the domain exists in its local cache. If the domain exists, the most recent record is first pushed into the memory before comparing the variation with the live record. If the domain is not found in the local cache, the browser calls an OS-specific library function to invoke a lookup. This library function (gethostbyname in widows) initially checks if the hostname is resolvable by referencing the local host file then attempts to resolve the hostname via DNS. In a situation where the library function is unable to find a cached version or the hosts file, a request is made to the default DNS server, which is usually the local router or the ISP‘s caching DNS server in other instances.

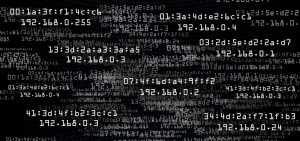

ARP Initialization

The target IP address is required by the network stack library to initiate an ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) broadcast, while the MAC address of the interface is required to send out the initializing ARP broadcast. The ARP cache is then looked up for an ARP entry for the target IP address. If an entry is found, a “Target IP = MAC” is returned. If the ARP entry is not in the cache, the routing table is looked up to check if the target IP is on any subnets on the local routing table. If a matching entry is found, the interface associated with that subnet is used by the library, else, the interface containing the subnet of the default gateway is utilized. The unique 48 bit MAC address of the NIC (Network Interface Card) is looked up. The network library sends an L2 (datalink) ARP request in the format:

Sender MAC (source): MM:MM:MM:SS:SS:SS

Sender IP address (source): #.#.#.#

Target MAC (dest): FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF (Broadcast)

Target IP address (dest): #.#.#.#

Computer Network Connectivity

Considering how devices can join the network via wired or wireless connectivity, the process of establishing the ARP request varies depending on what technology exists between the computer and the router, being the path to the internet. If the computer is DC (Directly connected) to the router, the router instantly responds with an ARP reply. If a hub (deprecated) is serially between the computer and the router, the hub sends broadcasts containing the ARP request out all other ports irrespective of their current status, establishing connectivity for the router based on serial topology. If the computer is DC to a switch, the switch then checks its local CAM/MAC table in an attempt to match a corresponding port with the MAC address in question. If no entry is found, the ARP request is rebroadcasted to all other ports.

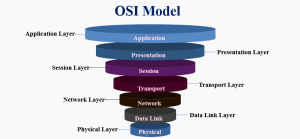

Opening of a socket

Since the network library now has the IP address of either the DNS server or the default gateway, the initial DNS process is resumed. If the response size exceeds the required size, TCP port 53 is opened to send a request to the DNS server, else, UDP is used. The browser then collates the IP address and port number of the destination server from the URL, makes a call to the system library function using the default port numbers depending on the protocols used (the HTTP: 80, HTTPS: 443), and requests a TCP socket stream named AF_INET/AF_INET6 (for IPv4 and IPv6 respectively)and SOCK_STREAM. This request first hits L4 (Transport Layer), where a TCP segment is created. The source port is chosen from within the kernel’s dynamic port range while the destination port is added to the header.

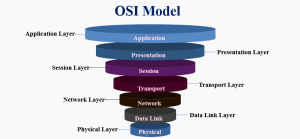

OSI Model downstream

The segment is sent to L3 (Network Layer) of the OSI model, which adds an IP header to the first segment. The destination server and the current machine IP address and is then converged to make up a packet. Next, the packet arrives at layer 2 (datalink Layer), alongside an additional frame header, which includes the MAC address of the machine’s NIC and the MAC address of the default gateway (local router). As previously addressed, if the know the MAC address of the gateway is unknown to the kernel, the kernel must broadcast another ARP query to find it.

At this stage, the packet is acknowledged and ready to be transmitted using most traditional media, including wifi(wireless), Ethernet cable(wired), or Cellular data network (wireless mobile devices).

LAN setup

Most SOHO (Small Office Home Office)or personal Internet connections involve packet movement from a computer, through a local network, and a modem (MOdulator/DEModulator), which converts binaries to an analog signal suitable for transmission via telephone (deprecated), cable, or wireless connections. On the ISP’s end of this connection is a similar modem reverses the analog signals back into digital data to be reprocessed by the next network node where the “from” and “to” addresses are further examined. If fiber optic or direct Ethernet connectivity is used, the data remains unchanged and is passed directly to the next network node for further examination. Dataflow

Dataflow

When the packet reaches the router managing the local subnet, it continues to travel to a collection of one or more IP prefixes run by one or more network operators that maintain a single, clearly-defined routing policy known as Autonomous Systems (AS). Each router on this path then extracts the destination address from the IP header and routes the traffic to the next appropriate hop. The TTL ( Time To Live) field embedded in the IP header continues to reduce by 1 for each router that successfully passes through. In the case of network congestion, where the current router has no space in its queue, or the TTL field reaches zero, the packet is dropped.

3-Way handshake

Following the TCP connection flow, the 3-way handshake is initialized. This involves the process of a client choosing an initial sequence number (ISN) and sending the packet to the server with the synchronize (SYN) sets. The server then receives the SYN request by choosing its ISN, Notifies SYN of this update, then copying the client ISN +1 to its ACK field with the addition of an ACK flag acknowledging the receipt of the initial packet. The client then acknowledges the connection by sending a packet containing an increased sequence and receiver acknowledgment number. On the source, SEQ is increased by the same number of data bytes. The recipient then sends an ACK packet, which is equal to the last received sequence from the source packet.

To close the current connection, the closing terminal sends a FIN packet while the recipient ACKs the FIN with its FIN, the closing terminal then ACKs the recipient’s FIN with its own ACK

CA (Certificate Authority)

The client computer sends a “ClientHello” plus its TLS version number to the server, the server then replies with a “ServerHello” message to the client with its TLS version, cipher mode, compression methods and the public certificate of the server, signed by a verifiable CA (Certificate Authority). In this certificate is a public key which the client uses to encrypt other unencrypted portion of the handshake before a mutual symmetric key is selected for use. The client then runs a verification of the server’s digital certificates against its list of trusted CAs. If trust is established, the client continues to generate a string of pseudo-random data encrypted with the server’s public key, which is used to determine the symmetric key type.

Key Infrastructure

The server then decrypts the random bytes using its private key. Next, it uses this data to generate a localized copy of the symmetric master key. At this point, the client sends an “end-of-message” notification to the server and encrypts the transmission with a symmetric key. The server accepts this message, generates its localized hash, decrypts the incoming hash from the client, and verifies a match with both hashes. If the hashes match, the server sends a finished message encrypted with the symmetric key to the client. If the hashes do not match, a certificate validity error is logged. The TLS session is then established for the transmission of encrypted application data using a chosen symmetric key algorithm (3DES, RC4, IDEA, CAST5…)

HTTP protocol

In the case where the web browser used was written by Google (Google Chrome), a negotiation request is sent to the server to upgrade the regular HTTP protocol to SPDY (pronounced speedy), as opposed to sending a usual HTTP request to retrieve the page. This is usually a GET /HTTP/1.1 request containing host: google.com and connection: close [other headers] where other headers comprise of single new lines of colon-separated series of key-value pairs in the format of the HTTP specification. HTTP/1.1 here is the signal showing that the connection closes as soon as the response completes.

Server Transaction

Upon fulfilling these deliverables, the server then receives a single blank new line from the web browser, which indicates a completion of the request. Next, the server replies with a response code stating the status of the request and corresponding response code, in this case, 200 OK. The server then decides to close the connection or keep it open

for more requests depending on whether the client’s header requested this information. After the HTML portion is parsed, this process is repeated for every other resource that is referenced within the HTML, which includes CSS, JS, image, and media. In this case, instead of GET / HTTP1.1, the request becomes GET /$(URL)HTTP/1.1. In some cases, the HTML can reference a resource hosted on another domain, then the browser repeats the process involving DNS modification of the hostname.

HTTP Server Request Handle

On the server-side, the HTTPD server or HTTP Daemon (which can be Apache or Nginx for Linux and IIS for Windows) handles all requests or responses from the client. As soon as the HTTPD receives the request,

The server breaks down the incoming request into three parameters;

HTTP Request Method (GET), Domain (google.com) and requested path (index, since no path/page is specified after “/”). The servers then verify the availability of a remote virtual host configured to resolve to google.com and verifies that the domain can accept GET requests. If the server is configured to use a rewrite module (URL Rewrite in IIS or mod_rewrite in Apache), the existing rewrite rule in the module is utilized, else, the server continues to pull content housed in the index folder, treating the URL as https://www.google.com/. The server then parses the content of this file and interprets the content of the index file to a process that outputs a user-readable format of the content.

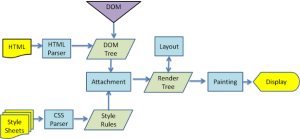

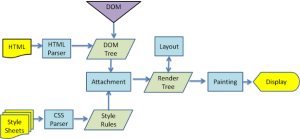

Browser rendering

The browser’s main functionality is requesting web resources from servers and presenting the output in an appropriate format, specified by the URI (Uniform Resource Identifier). Behind the scene, the server supplies the resources, including CSS, HTML, and media to the browser. The browser further refines these data by parsing the language/scripts, rendering the data by constructing a DOM (Document Object Model) tree, and eventually painting the render tree. HTML and CSS (maintained by the W3C ) specifies the way the browser interprets and displays HTML. Structurally, the web browser major comprises of the UI (User Interface), UI backend browser engine, render engine, Networking, Javascript engine, Data storage capability.

HTML parsing

The HTML parser, using built-in rendering capability, audits the HTML markup into a parse tree, which is a tree of DOM element attribute nodes. Because HTML cannot be parsed chronologically, the browser is forced to use a custom HTML parsing technique whose algorithm is determined by the HTML5 specification.

After these deliverables are met, the web browser begins the process of fetching external resources linked to the page, in the form of the layout (CSS), embedded scripts (Ajax, JS), and media (visuals). This raw file is marked as “in-progress” and parsing scripts are marked as “deferred”, which are resources awaiting execution after parsing is complete. When the document load state is complete, a load event is fired. In a situation where the browser encounters an error while loading an invalid content, the error state is logged in browser console but not directly visible to the end-user.

CSS interpretation and Page rendering

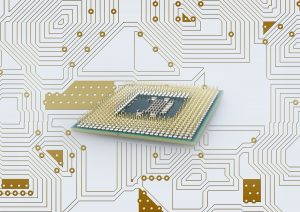

Using standard CSS lexicon and syntax containing CSS rules with selectors and objects, resources are parsed into a stylesheet object. This is a stateless activity as CSS parsers operate top-down or bottom-up, depending on the parser generator in use. The browser renders the page by creating a ‘Frame Tree’ and calculating the CSS style values for each node. Furthermore, the browser then calculates the preferred width, actual width, height, coordinates, textures, wrapping, margins, borders, and padding of each node in the ‘Frame Tree’ bottom-up using the standard CSS set rules. Next, it creates layers that describe what parts of the page can be logically grouped for animation without being re-rasterized. The CPU can either rasterize the transversed render objects for each layer or drawn on the GPU directly, using D2D/SkiaGL for rendering on the backend.

GPU Rendering

During rendering, the graphical computing layers either make use of a general-purpose CPU or the graphical processor’s GPU for advanced rendering. In cases where a refresh or reload command is triggered, the pre-existing values are used, excluding complex web applications where interactive user fields are present. The browser then refines the output using logical composite commands, which are enforced using hardware acceleration drivers like Direct3D/OpenGL. The GPU command buffer flushes for asynchronous rendering, and the frame is forwarded. After rendering, the browser finally executes other applicable scripts, including Flash (deprecated), interactive hardware plugins, and the requested query displays.

Other websites involving a process excerpt from the CIA (confidentiality, Integrity, Availability) triad including extended input parsing, language translation, form submission, password authentication, proxy/firewall network, and web application integration require a more sophisticated approach.

Browser input Logic

Browser input Logic

DNS lookup

DNS lookup

Dataflow

Dataflow